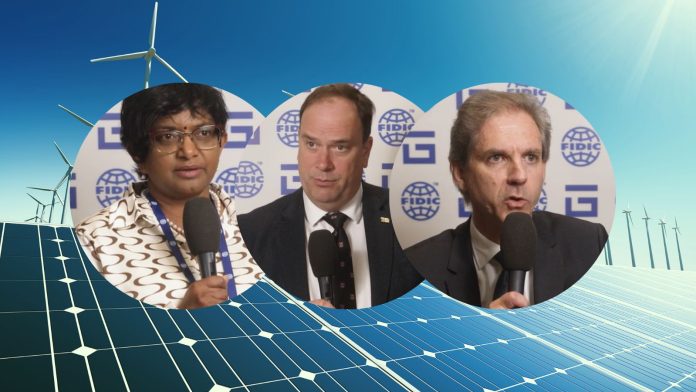

For net zero to succeed everywhere, a global approach to skills, investment and ideas is needed. We asked Chris Lewis, global head of infrastructure at EY, Malani Padayachee-Saman, CEO of MPAMOT and EFCA president, Benoît Clocheret, what that looks like.

Achieving net zero will involve every part of the world undertaking a dramatic change in infrastructure and the built environment. To do that on the scale required to halt climate change raises real questions about how we avoid leaving parts of the world behind.

In the past, the developing world has often struggled for skills and investment because skilled people are attracted to life in wealthier countries and finance is more readily available in developed economies. This could prove particularly acute with climate change, as rich nations rush to decarbonise, creating potential shortages of skills and finance on a global scale.

At the same time, however, there is a real awareness that on climate change, the whole world succeeds of fails together. That in turn may see greater attention paid to ensuring that progress in one place doesn’t hold back progress elsewhere.

Nowhere is this more crucial than skills. Malani Padayachee-Saman, founder of MPAMOT in Africa, said that this is not just an issue of existing engineering skills gaps. Industry needs to repurpose itself for the diverse and emerging skills needed for a net zero future.

If the industry doesn’t get that right, then infrastructure may find itself competing for more of its talent with other sectors, as well as continuing to compete for people within infrastructure too. That would in turn risk net zero being stalled wherever the contest for skills is lost. And there is a similar challenge with finance.

For many years, Africa in particular has faced real challenges in attracting sufficient investment for development, decarbonisation or economic growth. This has persisted despite growing evidence that Africa could provide a solution to global challenges like the energy transition and decarbonisation. Fortunately, Chris Lewis of EY thinks there may be a climate solution to this.

Speaking to Infrastructure Global at the Global Leadership Forum Summit, Lewis explained that the developing world can be helped to leapfrog carbon-intensive economic development and instead invest in creating a net zero economy without the legacy the developed world has.

In effect, he says that a great deal could be achieved more effectively if developing nations can completely halt the historic development pattern of high intensity carbon, before then gradually bringing carbon down later. As the technology for a low-carbon economy now exists, it would be efficient those countries to develop as low carbon economies .

Achieving that leapfrog will not be easy and the developed world remains something of a primary focus because of its high emissions compared to other nations. However, while the developed world makes some progress, the lessons learned and technologies deployed in wealthy countries can become the technologies deployed in developing nations too.

To make that happen, a sharing of knowledge across borders will be vital. Just as innovations benefit from those knowledge sharing, so countries can benefit from understanding the different conditions and challenges around the world. And for that, the world needs competitors to occasionally work collaboratively.

President of the European Federation of Engineering Consultancy Associations, Benoît Clocheret, explained that industry faces different issues in different continents, so sharing experiences from across the global industry is critical for climate action.

That can be hard but Clocheret said that industry wants to show that it can act collaboratively, even if it is made up of competitors, because the industry is acutely aware of fundamental issues facing the planet. But while a commitment to collaborate is positive, the industry will be judged by its actions.

That brings us back to the skills challenge. The effective brain drain from one country or continent to another is very well established throughout recent history and has taken a toll on the developing world before.

Padayachee-Saman stressed that it is very clear that to get skills right this time will require strong collaboration in context to avoid a brain drain and to establish collaborative initiatives for in-country skills development in the developing world.

A big reason for that will be that infrastructure has to meet local standards. So as net zero drives more projects in developing countries, it may prove harder to repurpose the skills of those who left for developing countries to come back to run projects. As a result, global sharing of experience will need to be matched by a similar effort to ensure each country has the capacity to develop ever-changing skills training.