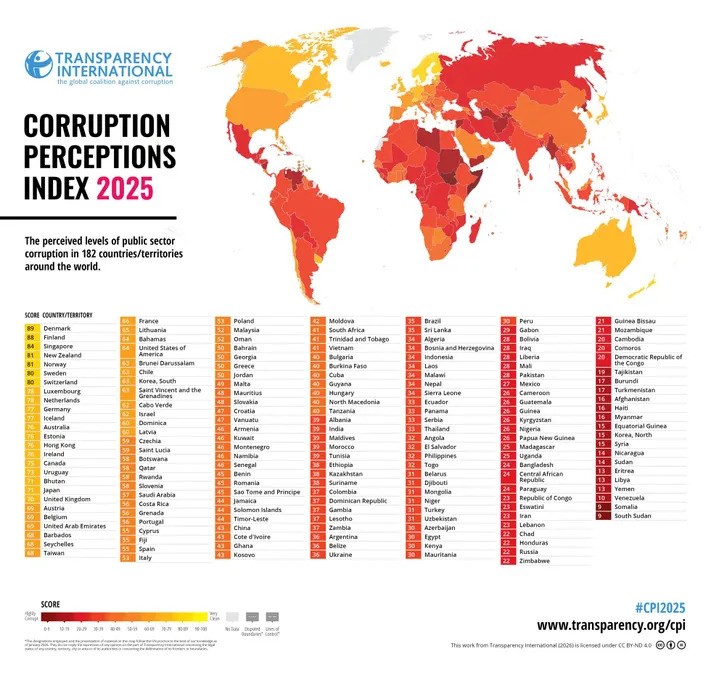

The 31st edition of Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index reveals a concerning picture of long-term decline in leadership to tackle corruption.

Corruption is worsening globally, with even established democracies experiencing rising corruption amid a decline in leadership, according to Transparency International’s recently published 2025 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). The annual index shows that the number of countries scoring above 80 has shrunk from 12 a decade ago to just five this year.

The data show that democracies, typically stronger on anti-corruption than autocracies or flawed democracies, are experiencing a worrying decline in performance. This trend spans countries such as the United States (64), Canada (75) and New Zealand (81), to various parts of Europe, like the United Kingdom (70), France (66) and Sweden (80). Another concerning pattern is increasing restrictions by many states on freedoms of expression, association and assembly. Since 2012, 36 of the 50 countries with significant declines in CPI scores have also experienced a reduction in civic space.

2025 saw a wave of anti-corruption protests led by Gen Z, mostly in countries in the bottom half of the CPI whose scores have largely stagnated or declined over the past decade. Young people in countries such as Nepal (34) and Madagascar (25) took to the streets to criticise leaders for abusing their power while failing to deliver decent public services and economic opportunity.

Transparency International is warning that the absence of bold leadership in the global fight against corruption is weakening international anti-corruption action and risks reducing pressure for reform in countries throughout the world.

François Valérian, chair of Transparency International said: “Corruption is not inevitable. Our research and experience as a global movement fighting corruption show there is a clear blueprint for how to hold power to account for the common good, from democratic processes and independent oversight to a free and open civil society. At a time when we’re seeing a dangerous disregard for international norms from some states, we’re calling on governments and leaders to act with integrity and live up to their responsibilities to provide a better future for people around the world.”

Transparency International is calling for: –

- Renewed political leadership on anti-corruption, including the full enforcement of laws, implementation of international commitments and reforms that strengthen transparency, oversight and accountability.

- Protection of civic space, by ending attacks on journalists, NGOs and whistleblowers and stopping efforts to restrict independent civil society work.

- Close the secrecy loopholes that let corrupt money move across borders, including by reining in professional gatekeepers and ensuring transparency on who really owns companies, trusts and assets.

Decline in leadership against corruption

In many European countries, anti-corruption efforts have largely stalled over the past decade. Since 2012, 13 countries in western Europe and the EU have significantly declined and only seven have significantly improved. In December 2025, the EU agreed its first Anti-Corruption Directive to harmonise criminal laws on corruption. What could have been a zero-tolerance framework was watered down by some member states, including Italy (53), which blocked the criminalisation of public officials’ abuse of office. The result, according to Transparency International, is a framework that lacks ambition, clarity and enforceability.

The United States (64) sustained its downward slide to its lowest-ever score. Although 2025 developments are not yet fully reflected, actions targeting independent voices and undermining judicial independence raise serious concerns. Beyond the CPI findings, the temporary freeze and weakening of enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act signal tolerance for corrupt business practices, says Transparency International, while cuts to US aid for overseas civil society have weakened global anti-corruption efforts. Political leaders elsewhere have taken this as a cue to further restrict NGOs, journalists and other independent voices.

High CPI scores do not guarantee that countries are corruption-free, as several top-scoring nations enable corruption in other countries by facilitating the laundering and transfer of proceeds of corruption across borders, which the CPI does not cover. For example, Switzerland (80) and Singapore (84) are among the top scorers but have faced scrutiny for facilitating the movement of dirty money.

Global corruption key findings

The CPI ranks 182 countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption on a scale of zero (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean). The global average score stands at 42 out of 100, its lowest level in more than a decade, pointing to a concerning downward trend that will need to be monitored over time.

According to the Corruption Perceptions Index, the vast majority of countries are failing to keep corruption under control, with more than two-thirds – 122 out of 180 – scoring under 50. For the eighth year in a row, Denmark obtains the highest score on the index (89) and is closely followed by Finland (88) and Singapore (84). Countries with the lowest scores overwhelmingly have severely repressed civil societies and high levels instability like South Sudan (9), Somalia (9) and Venezuela (10).

Since 2012, 50 countries have seen their scores significantly decline in the index: those which dropped the most include Türkiye (31), Hungary (40) and Nicaragua (14). The report says that this reflects a decade-long, structural weakening of integrity mechanisms, fuelled by democratic backsliding, conflict, institutional fragility and entrenched patronage networks. “These declines are sharp, enduring and difficult to reverse, as corruption becomes systemic and deeply embedded in both political and administrative structures,” the report claims.

Since 2012, 31 countries have significantly improved their scores on the index. Among the biggest improvers were Estonia (76), South Korea (63) and Seychelles (68). The long-term improvements in democratic countries like these reflect sustained momentum with reforms, strengthened oversight institutions and broad political consensus in favour of clean governance. Success in these areas has been attributed to among other things, digitising public services, professionalising the civil service and embedding regional and global governance standards.